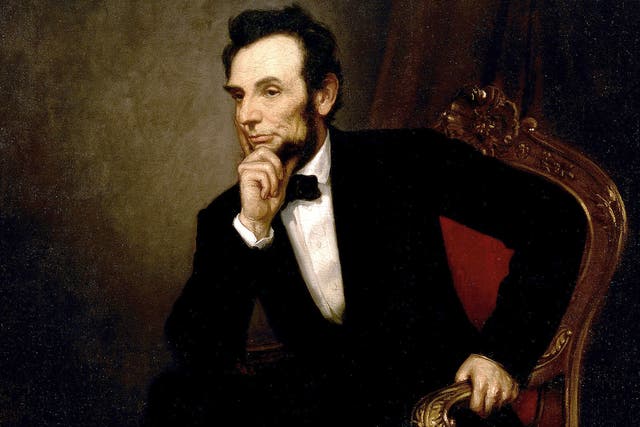

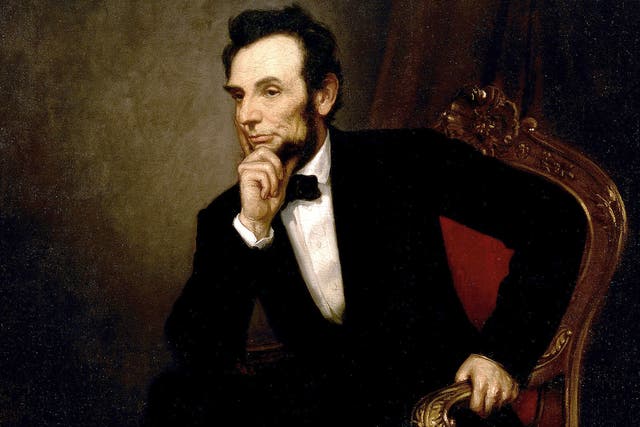

Abraham Lincoln, a self-taught lawyer, legislator and vocal opponent of slavery, was elected 16th president of the United States in November 1860, shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. Lincoln proved to be a shrewd military strategist and a savvy leader: His Emancipation Proclamation paved the way for slavery’s abolition, while his Gettysburg Address stands as one of the most famous pieces of oratory in American history.

In April 1865, with the Union on the brink of victory, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln’s assassination made him a martyr to the cause of liberty, and he is widely regarded as one of the greatest presidents in U.S. history.

Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, to Nancy and Thomas Lincoln in a one-room log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky. His family moved to southern Indiana in 1816. Lincoln’s formal schooling was limited to three brief periods in local schools, as he had to work constantly to support his family.

In 1830, his family moved to Macon County in southern Illinois, and Lincoln got a job working on a river flatboat hauling freight down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. After settling in the town of New Salem, Illinois, where he worked as a shopkeeper and a postmaster, Lincoln became involved in local politics as a supporter of the Whig Party, winning election to the Illinois state legislature in 1834.

Like his Whig heroes Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, Lincoln opposed the spread of slavery to the territories, and had a grand vision of the expanding United States, with a focus on commerce and cities rather than agriculture.

Rugged conditions. Heavy labor. Minimal schooling. And a mother gone too soon.

In 1861, Kate Warne kept the president‑elect safe from an assassination plot on his train journey to Washington.

The 16th U.S. president was firm in believing slavery was morally wrong, but his views on racial equality were sometimes more complicated.

Lincoln’s profile rose even higher in early 1860 after he delivered another rousing speech at New York City’s Cooper Union. That May, Republicans chose Lincoln as their candidate for president, passing over Senator William H. Seward of New York and other powerful contenders in favor of the rangy Illinois lawyer with only one undistinguished congressional term under his belt.

In the general election, Lincoln again faced Douglas, who represented the northern Democrats; southern Democrats had nominated John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky, while John Bell ran for the brand new Constitutional Union Party. With Breckenridge and Bell splitting the vote in the South, Lincoln won most of the North and carried the Electoral College to win the White House.

He built an exceptionally strong cabinet composed of many of his political rivals, including Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates and Edwin M. Stanton.

After years of sectional tensions, the election of an antislavery northerner as the 16th president of the United States drove many southerners over the brink. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated as 16th U.S. president in March 1861, seven southern states had seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America.

Lincoln ordered a fleet of Union ships to supply the federal Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April. The Confederates fired on both the fort and the Union fleet, beginning the Civil War. Hopes for a quick Union victory were dashed by defeat in the Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), and Lincoln called for 500,000 more troops as both sides prepared for a long conflict.

While the Confederate leader Jefferson Davis was a West Point graduate, Mexican War hero and former secretary of war, Lincoln had only a brief and undistinguished period of service in the Black Hawk War (1832) to his credit. He surprised many when he proved to be a capable wartime leader, learning quickly about strategy and tactics in the early years of the Civil War, and about choosing the ablest commanders.

General George McClellan, though beloved by his troops, continually frustrated Lincoln with his reluctance to advance, and when McClellan failed to pursue Robert E. Lee’s retreating Confederate Army in the aftermath of the Union victory at Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln removed him from command.

During the war, Lincoln drew criticism for suspending some civil liberties, including the right of habeas corpus, but he considered such measures necessary to win the war.

Shortly after the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg), Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, and freed all of the enslaved people in the rebellious states not under federal control, but left those in the border states (loyal to the Union) in bondage.

Though Lincoln once maintained that his “paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery,” he nonetheless came to regard emancipation as one of his greatest achievements and would argue for the passage of a constitutional amendment outlawing slavery (eventually passed as the 13th Amendment after his death in 1865).

Two important Union victories in July 1863—at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and at the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania—finally turned the tide of the war. General George Meade missed the opportunity to deliver a final blow against Lee’s army at Gettysburg, and Lincoln would turn by early 1864 to the victor at Vicksburg, Ulysses S. Grant, as supreme commander of the Union forces.

In November 1863, Lincoln delivered a brief speech (just 272 words) at the dedication ceremony for the new national cemetery at Gettysburg. Published widely, the Gettysburg Address eloquently expressed the war’s purpose, harking back to the Founding Fathers, the Declaration of Independence and the pursuit of human equality. It became the most famous speech of Lincoln’s presidency, and one of the most widely quoted speeches in history.

In 1864, Lincoln faced a tough reelection battle against the Democratic nominee, the former Union General George McClellan, but Union victories in battle (especially General William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in September) swung many votes the president’s way. In his second inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1865, Lincoln addressed the need to reconstruct the South and rebuild the Union: “With malice toward none; with charity for all.”

As Sherman marched triumphantly northward through the Carolinas after staging his March to the Sea from Atlanta, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9. Union victory was near, and Lincoln gave a speech on the White House lawn on April 11, urging his audience to welcome the southern states back into the fold. Tragically, Lincoln would not live to help carry out his vision of Reconstruction.

Abraham Lincoln was disappointed by most of his generals—but not Ulysses S. Grant.