Jon Brodkin - Jan 15, 2018 5:54 pm UTC

Municipal broadband networks generally offer cheaper entry-level prices than private Internet providers, and the city-run networks also make it easier for customers to find out the real price of service, a new study from Harvard University researchers found.

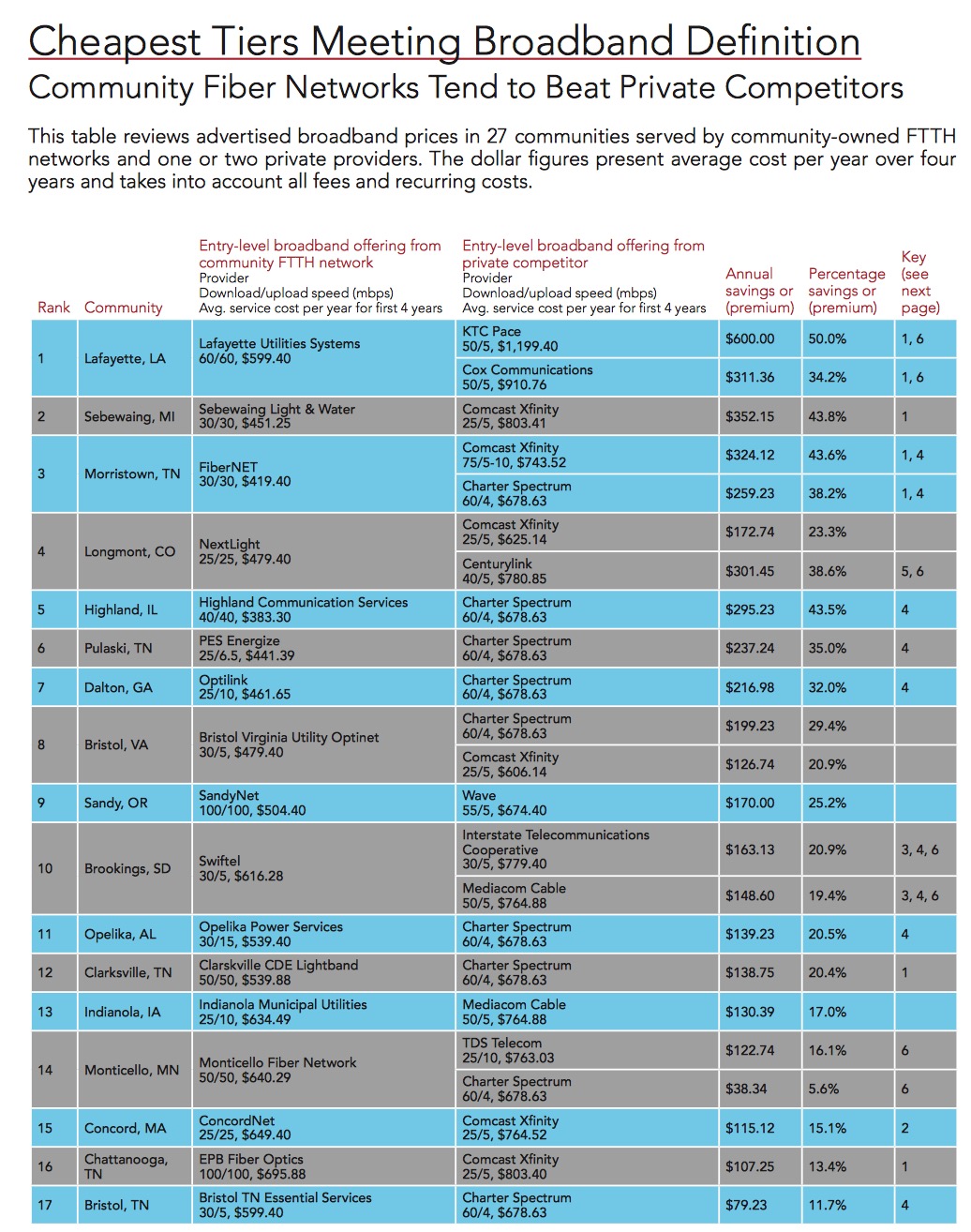

Researchers collected advertised prices for entry-level broadband plans—those meeting the federal standard of at least 25Mbps download and 3Mbps upload speeds—offered by 40 community-owned ISPs and compared them to advertised prices from private competitors.

The report by researchers at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard doesn't provide a complete picture of municipal vs. private pricing. But that's largely because data about private ISPs' prices is often more difficult to get than information about municipal network pricing, the report says.

In cases where the researchers were able to compare municipal prices to private ISP prices, the city-run networks almost always offered lower prices. This may help explain why the broadband industry has repeatedly fought against the expansion of municipal broadband networks. This fight includes pushing legislators to draft anti-municipal broadband state laws, lobbying against local ballot initiatives, and filing lawsuits against cities that build their own networks.

The Berkman Klein Center report says:

We found that most community-owned FTTH [fiber-to-the-home] networks charged less and offered prices that were clear and unchanging, whereas private ISPs typically charged initial low promotional or "teaser" rates that later sharply rose, usually after 12 months. We were able to make comparisons in 27 communities. We found that in 23 cases, the community-owned FTTH providers' pricing was lower when averaged over four years. (Using a three year-average changed this fraction to 22 out of 27.) In the other 13 communities, comparisons were not possible, either because the private providers' website terms of service deterred or prohibited data collection or because no competitor offered service that qualified as broadband. We also made the incidental finding that Comcast offered different prices and terms for the same service in different regions.

Researchers accounted for "all fees and recurring costs" in calculating the four-year averages.

In communities where municipal prices were lower than those charged by private ISPs, prices from municipal ISPs "were between 2.9 percent and 50 percent less than the lowest-cost such service offered by a private provider (or providers) in that market," the study said. "In the other four cases, a private provider's service cost between 6.9 percent and 30.5 percent less."

The biggest disparity found was in Lafayette, Louisiana, where the Lafayette Utilities Systems offered a 50 percent savings compared to KTC Pace and a 34.2 percent savings compared to Cox. The municipal provider's prices were better, even though its entry-level broadband speeds were 60Mbps down and 60Mbps up, while the entry-level KTC Pace and Cox plans offered 50Mbps down and just 5Mbps up.

In Sebewaing, Michigan, the municipal provider was 43.8 percent cheaper than Comcast, despite offering faster speeds in the entry-level broadband tier. Municipal providers beat the pricing of Comcast, Charter, Wave, and Mediacom in other cities.

The raw data used in the Harvard report is available here. Check out page 8 of the report to see the full version of this chart and footnotes:

The researchers chose the communities included in the report from data collected by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR), which has identified about 400 community-owned networks in the US.

"We focused specifically on 40 community networks on the ILSR's list that offer fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) service—as opposed to service from DSL, coaxial cable, or hybrid technology," the study said.

It's impressive that community-run fiber networks are so often cheaper than private cable services, for several reasons outlined in the report: "We reasoned that a targeted study of community-owned FTTH networks provided a valid subset and would be fair to the local private competitors because fiber is the most expensive technology to deploy and would have been installed more recently (with capital costs still being paid off in many cases). In addition, fiber—the most advanced and versatile technology—is the likely choice for any future network construction."

The report was written as part of the Berkman Klein Center's Responsive Communities Initiative.

There are caveats in the report, notably that it doesn't include pricing from AT&T and Verizon. "We did not collect data from AT&T because of prohibitions contained in the terms of service posted on AT&T's website," and "we did not collect data from Verizon because of prohibitions contained in the terms of service posted on Verizon's website," the report says.

AT&T's terms of service prohibit "systematically collect[ing] and us[ing] any Content including the use of any data mining, or similar data gathering and extraction methods." Verizon's terms say that "authorized use of this page is limited to the review of service availability information, for a particular address or phone number, solely by persons interested in purchasing Verizon service or making changes to existing Verizon service."

While it is possible to get some pricing information from these ISPs' websites, the study authors chose not to use it based on legal advice they received, coauthor David Talbot told Ars. AT&T and Verizon service plan and pricing information might not have changed the results too much, because the companies' networks often use DSL service that falls short of the FCC's broadband speed standard of 25Mbps/3Mbps.

Moreover, exact pricing information is hard to get from these companies' websites unless you type a specific address into availability checkers. The data is "only available if you plug in addresses and violate terms of service," Talbot told Ars. "And in most of the handful of towns where there was a terms of service issue, it involved DSL service anyway, so we think it's unlikely to change the overall outcome."

Talbot and his co-authors also aren't impressed by the Federal Communications Commission's data collection.

"In general we found that making comprehensive pricing comparisons among US Internet service plans is extraordinarily difficult. The US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) does not disseminate pricing data or track broadband availability by address," the report said.

The transparency of municipal broadband pricing is one of the key advantages the networks offer over many private ISPs.

"Of the 35 private Internet access plans we encountered in our data collection, 25 offered low-cost initial promotional (or 'teaser') rates and then increased the rate substantially at the conclusion of the initial period (typically 12 months)," the report said. "By contrast, we encountered only three examples of promotional pricing among the community-owned ISPs we studied. And MINET, in the towns of Monmouth and Independence, Oregon, was the only one to offer such a deal on a plan offering Internet access only, in the form of a special promotion for students."

The FCC's 2015 net neutrality order required all ISPs to be more transparent about pricing and data caps, but the Republican-led repeal of those rules last month also threw out the enhancements to transparency requirements.

UPDATE: Some commenters have asked whether building municipal broadband networks raises tax dollars. While that isn't addressed in the Harvard study, it's a topic we've covered several times. "Most [municipal] networks sell bonds to private investors who are repaid by revenues from the network. No taxpayer dollars," Christopher Mitchell, director of the ILSR's Community Broadband Networks Initiative, told us in this 2014 story. Network revenue often ends up subsidizing other municipal services.

For specific examples of network financing, see our previous stories that describe network projects in Fort Collins, Colorado, Sandy, Oregon, and Chattanooga, Tennessee.

You can find more information in an ISLR report titled, Correcting Community Fiber Fallacies.

The studied the listed prices, but I didn't see how much tax money was used to subsidize the service. Without the information, the actual cost to the citizens is unknown.

Most civic broadband services bring money into the city. The difference is, they don't ship most of that money to out of state corporate headquarters to pay for yet another corporate jet to fly the top corporate executives to yet another corporate golf retreat on some private tropical corporate island.

2078 posts | registered 2/2/2008 bburdge Ars Scholae PalatinaeThe studied the listed prices, but I didn't see how much tax money was used to subsidize the service. Without the information, the actual cost to the citizens is unknown.

Well, I can't speak for all the locations, but I live in Longmont, CO, and the tax money used is 0. The municipal power company issued bonds (with voter permission, and the city would cover the bonds in the event that the fiber company defaults) to pay for the build out, and the bonds are being repaid by the subscription fees.

Given that subscriber penetration has already far exceeded minimum necessary to be viable, there's no sign that tax payers will ever pay a penny on it.

It's also worth noting that for Longmont the table doesn't give the whole story - there is a 25/25Mb option for those who don't need much speed, but for a 4 year average of 750/year you can get 1Gb/1Gb service.

1064 posts | registered 9/21/2013The studied the listed prices, but I didn't see how much tax money was used to subsidize the service. Without the information, the actual cost to the citizens is unknown.

Most civic broadband services bring money into the city. The difference is, they don't ship most of that money to out of state corporate headquarters to pay for yet another corporate jet to fly the top corporate executives to yet another corporate golf retreat on some private tropical corporate island.

2078 posts | registered 2/2/2008 bburdge Ars Scholae PalatinaeThe studied the listed prices, but I didn't see how much tax money was used to subsidize the service. Without the information, the actual cost to the citizens is unknown.

Well, I can't speak for all the locations, but I live in Longmont, CO, and the tax money used is 0. The municipal power company issued bonds (with voter permission, and the city would cover the bonds in the event that the fiber company defaults) to pay for the build out, and the bonds are being repaid by the subscription fees.

Given that subscriber penetration has already far exceeded minimum necessary to be viable, there's no sign that tax payers will ever pay a penny on it.

It's also worth noting that for Longmont the table doesn't give the whole story - there is a 25/25Mb option for those who don't need much speed, but for a 4 year average of 750/year you can get 1Gb/1Gb service.

1064 posts | registered 9/21/2013Jon Brodkin Jon is a Senior IT Reporter for Ars Technica. He covers the telecom industry, Federal Communications Commission rulemakings, broadband consumer affairs, court cases, and government regulation of the tech industry.